At Optics11 Life, we want to highlight the researchers advancing mechanobiology and 3D cell models. Faces of Mechanobiology is a guest series featuring researchers who apply mechanical insights and tools to reveal how cells sense, respond, and function in complex environments.

In this first feature, Dr. Angelo Accardo (Associate Professor at Delft University of Technology) explores how light-assisted 3D fabrication, including two-photon polymerization (2PP) and micro-digital light processing (μDLP), can create biomimetic microenvironments with tunable mechanics and precisely defined architectures. He highlights stiffness-tunable hydrogels, shape-morphing microstructures, topography-guided neuronal organization, and millimetre-scale gyroid scaffolds for 3D neural culture, showcasing how microfabrication is expanding what’s possible in 3D mechanobiology.

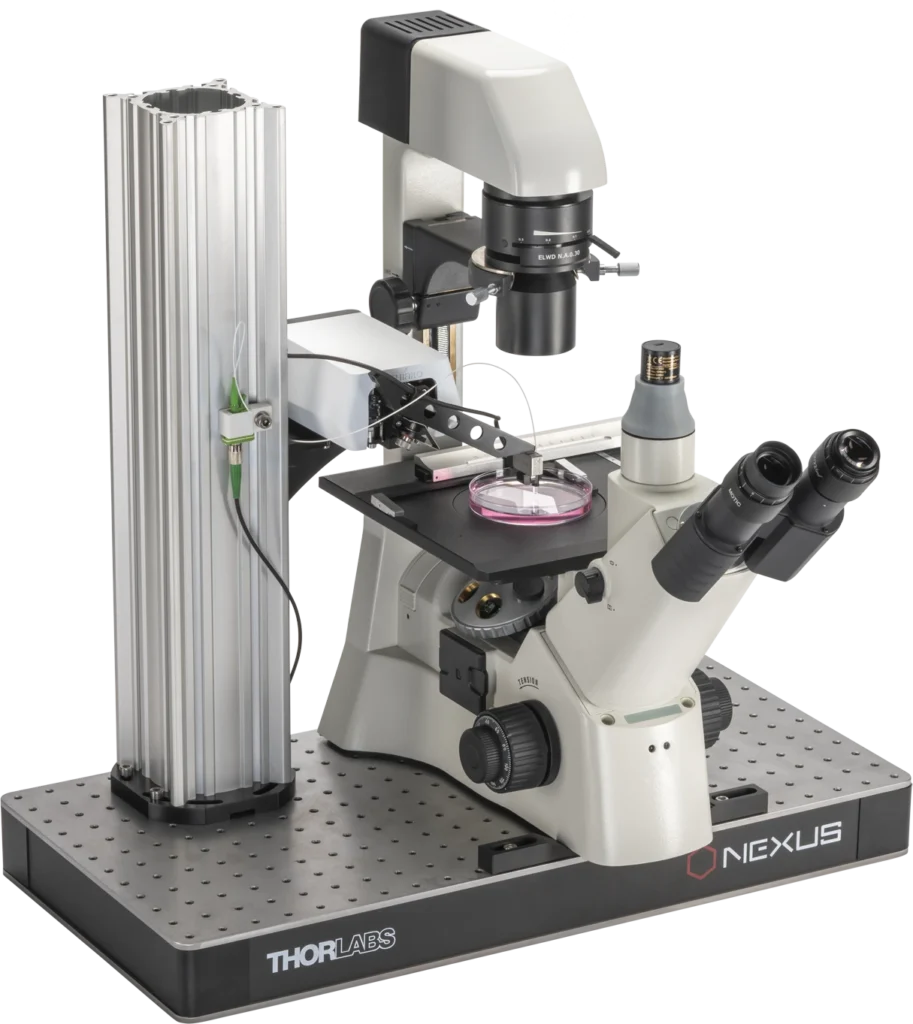

In his research, Dr. Accardo has used both Optics11 Life’s Piuma Nanoindenter as well as Chiaro Nanoindenter for mechanical characterization.

Unleashing light-assisted 3D fabrication for cell mechanobiology

Our body is composed of unit blocks: organs, tissues and, ultimately, cells. Understanding the functioning of cells in health and disease plays a fundamental role, however, current cell biology protocols are limited to 2D cultures, which, although inexpensive and easy to handle, do not reproduce the complexity of real tissues. The realization of biomimetic microenvironments is crucial for the development of tissue engineering and in vitro drug screening strategies1.

Indeed, creating favorable conditions for cell growth, migration and functional interplay with their surroundings involves several approaches in different fields, including biochemistry, neurosciences, physics, nanotechnology, microfluidics, and mechanobiology. In the last two decades, this multidisciplinary activity led to the blooming of numerous strategies aiming at creating architectures that mimic the topological, biochemical and mechanical properties of the natural extracellular matrix present in the tissues of our body.

In my group, we use light-assisted fabrication techniques to realize nano-, micro- and meso-scale environments for applications ranging from fundamental mechanobiology to in-vitro disease/treatment modeling and tissue engineering. The main manufacturing technology behind our scaffold models is two-photon polymerization (2PP), a technique able to achieve sub-micrometric feature resolution and 3D free-standing geometries without sacrificial supports.

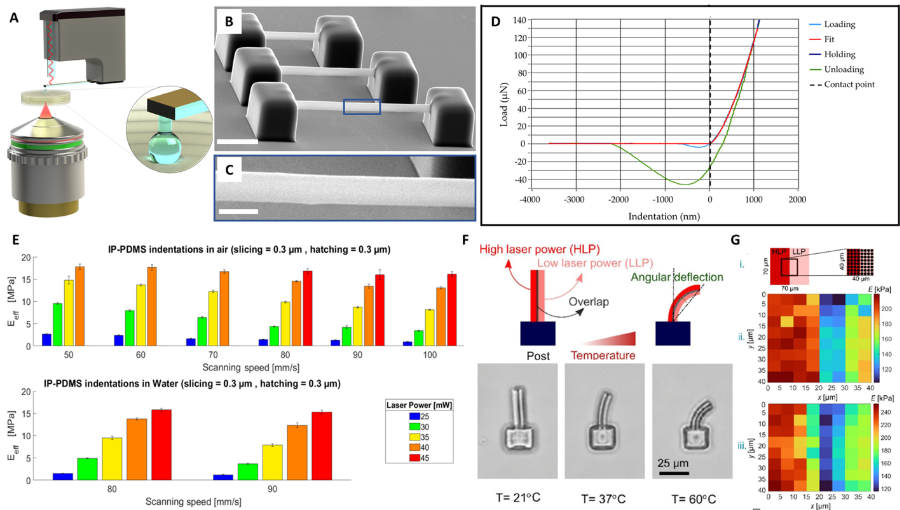

One of the peculiarities of this technique, is the ability to tune the Young’s modulus (YM) of the photopolymerized material by adapting the fabrication parameters. Varying the YM is an important feature as it can directly influence cell migration, differentiation and proliferation. As we recently demonstrated, 2PP can be effectively used to tune the YM of hydrogel2 and elastomeric materials (i.e., IP-PDMS) 3D free-standing microstructures (down to ≈ 1 µm) from kPa to MPa range3, measured via nanoindentation (Figure 1A-D). In addition, we showed that, on average, immersion in water lowered the YM by 5.4%, a very important point as in the context of cell biology applications, the material must be employed within an aqueous environment (Figure 1E).

This feature assumes a great relevance also in the realm of the “4th” dimension. Here, in order to incorporate programmable shape-morphing capability, we systematically studied how 2PP 3D printing parameters (e.g., laser power, scanning speed) and the chemical composition of a well-established temperature-responsive hydrogel, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM), influence the shape morphing of bilayer microstructures4 within a temperature range of ~ 32 °C to 60 °C (Figure 1F,G). These microarchitectures served as proof-of-concept actuators, demonstrating the potential of programmable stimuli-responsive 3D microscale soft robotics and microfluidic systems.

Figure 1. A: Schematic of 2PP fabrication and optical interferometry-based nanoindentation of soft biomaterials; B,C: SEM micrographs of 2PP-printed IP-PDMS beams3; D: Typical load/indentation plot with Hertzian fit3; E: Influence of the scanning speed on the effective Young’s modulus of IP-PDMS in air and water3; F: Schematic drawing showing the bending of a 4D-printed bilayer beam from a single material (i.e., pNIPAM hydrogel) and its angular deflection at different temperatures of 21 °C, 37 °C, and 60 °C4; G: YM measurements across the bilayer 2PP printed pNIPAM hydrogel beam4.

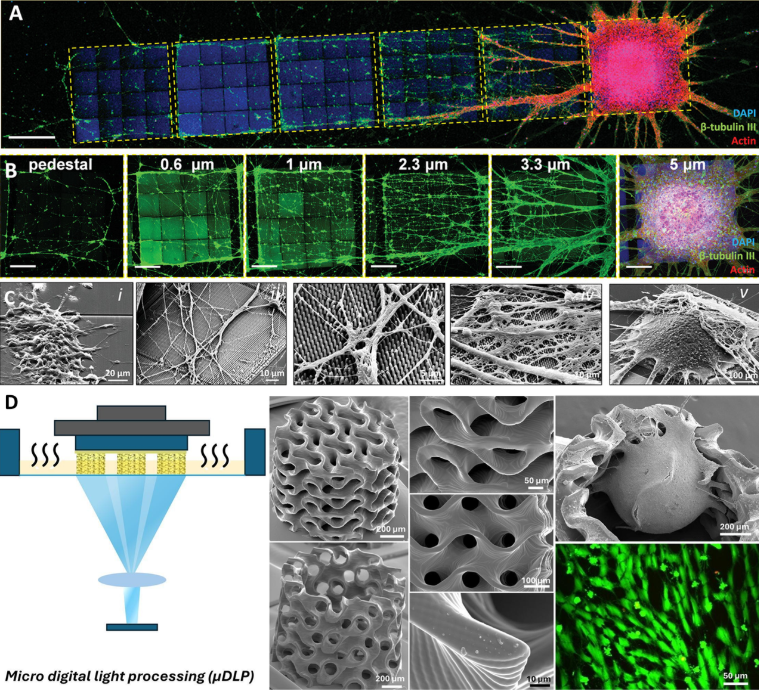

In the field of mechanobiology, tuning the intrinsic YM of the employed biomaterial is not the only option to steer cell fate. In another recent work from my group we made use of the effective shear modulus mechanism to assess the influence of topographic and mechanical cues on neuronal growth cones (NGCs) and network directionality in 3D-engineered cell culture models5.

This parameter represents the shear modulus sensed by cells when crawling on top of micro- or nano-structures’ arrays and is directly influenced by the aspect ratio of the nanostructures. Taller/slender nanostructures bend more easily, thus providing a softer “perceived” rigidity. 2PP was employed to fabricate nanopillar arrays featuring tunable effective shear modulus (0.5-35 MPa) and diameter close to the one of filopodia (200-400 nm). The nanopillar arrays were seeded with different neuronal cell lines, including neural progenitor cells (NPCs) derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), I3Neurons, or primary hippocampal neurons.

All cell types exhibited preferential orientations according to the nanopillar topology, as shown by neurites creating a high number of oriented orthogonal networks. We systematically observed also the formation of a single neurosphere on the tallest nanopillar array, which is the one featuring the lowest effective shear modulus (0.5 MPa). Several neurites sprouted as large bundles from the neurosphere, extending toward both the other arrays and the glass substrate (Figure 2A-C).

Figure 2. A-C: Neurosphere and neurites sprouting on nano-pillar arrays featuring tunable effective shear modulus5; D: µDLP fabrication of PEGDA/GelMA hydrogel meso-scale scaffolds for hybrid scaffold-free/scaffold-based neural organoid culture6.

While 2PP provides the highest achievable feature resolution, it has limitations in terms of overall scaffold size and fabrication speed. This can play a significant role when the target is to host the growth of large-scale tissue-like structures. To this aim, we recently reported a high-resolution micro-digital light processing (μDLP) 3D printing protocol for fabricating soft PEGDA/GelMA hydrogel scaffolds featuring mesoscale millimetre-sized gyroid-based architectures tailored for 3D neural cell culture6 (Figure 2D).

In contrast to 2PP, μDLP employs a layer-by-layer approach that enables faster production of larger structures. Typical DLP printers have a feature resolution of 50–80 μm, whereas μDLP printers, such as the one employed in this study, could achieve a feature resolution of approximately 15 μm. This was possible by the use of additional optics after the digital micromirror device, which reduces the total projection area and increases precision. The mechanical properties of the resulting hydrogel structures showed a Young’s modulus (YM) in the 770 kPa – 2.25 MPa range, depending on the presence of GelMA, thus very relevant for neural cells (brain YM in the kPa range), along with remarkable biocompatibility (≈80 % cell viability). The hybrid scaffold-free/scaffold-based approach enabled strong cell adhesion and organoid sprouting, paving the way for further research into necrotic core formation, electrophysiological activity, genetic expression, and neural maturation markers.

References

1) Accardo, A.; Lemma, E. D. Editorial Overview: Scaffold-Based and Scaffold-Free Approaches for Mechanobiology, in Vitro Disease Modeling and Treatment. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 2025, 35, 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobme.2025.100609.

(2) Costa, B. N. L.; Adão, R. M. R.; Maibohm, C.; Accardo, A.; Cardoso, V. F.; Nieder, J. B. Cellular Interaction of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Polymer and Hydrogel 3D Microscaffold Templates. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022, 14 (11), 13013–13024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c23442.

(3) van Altena, P. F. J.; Accardo, A. Micro 3D Printing Elastomeric IP-PDMS Using Two-Photon Polymerisation: A Comparative Analysis of Mechanical and Feature Resolution Properties. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15 (8), 1816. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15081816.

(4) Yarali, E.; Mubeen, A. A.; Cussen, K.; van Zanten, L.; Moosabeiki, V.; Zadpoor, A. A.; Accardo, A.; Mirzaali, M. J. Two-Photon Polymerization Based 4D Printing of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel Microarchitectures for Reversible Shape Morphing. Sci Rep 2025, 15 (1), 21549. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06269-2.

(5) Flamourakis, G.; Dong, Q.; Kromm, D.; Teurlings, S.; van Haren, J.; Allertz, T.; Smeenk, H.; de Vrij, F. M. S.; Tas, R. P.; Smith, C. S.; Brinks, D.; Accardo, A. Deciphering the Influence of Effective Shear Modulus on Neuronal Network Directionality and Growth Cones’ Morphology via Laser‐Assisted 3D‐Printed Nanostructured Arrays. Adv Funct Mater 2025, 35 (5). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202409451.

(6) van Altena, P. F. J.; Castillo Ransanz, L.; Manco, M.; Heine, V. M.; Accardo, A. Micro-Digital Light Processing of Conventional and Hollow Gyroid Mesoscale Hydrogel Scaffolds for Neural Cell Cultures. Micro and Nano Engineering 2025, 28, 100310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mne.2025.100310.

Dr. Angelo Accardo is an Associate Professor at the Department of Precision and Microsystems Engineering of Delft University of Technology, Coordinator of the Bio-Optomechatronics Lab, co-founder of the Delft Young Academy, committee member of the Delft Bioengineering Institute, member of the Holland Proton Therapy Center Programmaraad (Program Board), Scientific Steering Committee Member of the International Micro and Nanoengineering Conference, Treasurer/Board member of the International Micro and Nano Engineering Society and Associate Editor of the Elsevier Micro and Nano Engineering journal. By exploiting high-resolution light-assisted 3D additive manufacturing techniques (i.e., two-photon polymerization, stereolithography, micro-digital light processing), he creates engineered polymeric/hydrogel microenvironments for fundamental mechanobiology, in vitro disease/treatment modeling and tissue engineering applications involving brain (e.g., microglia, iPSCs-derived/primary neurons), (peri)vascular (e.g., brain microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes), cancer (e.g., glioblastoma), or bone (e.g. preosteoblasts) cells. He is author of 60+ publications in peer-reviewed journals, and was awarded several prizes and grants by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Link to Dr. Angelo Accardo’s personal page

Interested in participating? Send an email to marketing@optics11life.com

Mentioned in this article:

Chiaro

Chiaro is a microscope-compatible, nanoindentation system that allows you to combine unique mechanical insights with the imaging equipment of your choice. A compact yet powerful instrument to expand your lab infrastructure.

Piuma

The Piuma nanoindenter is a benchtop device designed to measure the mechanical properties of large tissues, biomaterials, and hydrogels at cell length scales.